Is Print Dead?

“Is Print Dead?” is an ongoing research project interrogating the title question and advocating for the value of printed media in a post-digitalized world. As a visual presentation of my research, I will document and analyze printed media as a curated object, art form, and artifact through images and essays.

A Brief History

To trace the course of printed media through the rapid digitalization of the last thirty years, it is helpful to give historical context to its lasting impact and modern manifestation. Developed by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440, the first printing press was revolutionary in the progression of communication networks and has been vital to the globalization which followed—eventually leading to the era of digitalization which we currently find ourselves.

With the development of the printing press, information was no longer guarded in a vault of elitism; for the first time in history, thousands of readers could engage with printed texts due to their ability to be mass produced and distributed. This spurred both the Reformation and the period of intellectual, technological, and artistic advancement that was the Renaissance, as print “encouraged disseminations, discourse, and debate…[becoming] an idea-generating process in and of itself” (Wheeler 44). In the centuries following, print would not only come to be an artifact of acquired knowledge, but an increasingly refined media central to all forms of communication—a media which facilitated and followed humanity through Darwinian evolution.

By the 1990s, the natural evolution of Gutenberg’s innovation would lead to the development of a new technology, a communication network to redefine human networking: namely, the Internet. By the time the Federal Networking Council legitimized the Internet in 1995, passing a resolution to officially define the term “internet”, the networking technology had already amassed 10 million global users (“A Short History of the Internet | National Science and Media Museum”).

As in Gutenberg’s day, a revolutionary step in the advancement of communication networks was in procession. However, the trend of digitalization which accompanied the Internet posed a dilemma. Here was a networking technology heralded for all which Gutenberg’s printing press originally was, providing all the same functions but to a greater degree. Where Gutenberg’s print could reach thousands of readers in a matter of days, the Internet could reach millions of readers instantaneously. Where Gutenberg’s press was efficient in mass producing publications, the Internet could reproduce itself indefinitely due to the lack of required physical materials (paper and ink) and manual labor (printing press technicians).

As we entered an era of digitalization, the question of whether printed media would be stripped of its value and function when faced with the existence of digital media was on the minds of many individuals, particularly those tied to the printing industry. After centuries of influence and historical impact, could print really be dead?

Vault is both literal and metaphorical in this regard. In his book “From Gutenberg to Google: The History of Our Future”, Tom Wheeler discusses the communication networks of the medieval world when knowledge was recorded in manuscripts. These manuscripts were guarded from the general population through several ways; first, one had to have access to the libraries in which they resided, and second, one had to be literate in the language of the manuscript. “The Establishment”, a group of high-ranking nobles and priests, facilitated the production and maintenance of these manuscripts, thus perpetuating their positions in society. In this way, “the Establishment was able to construct both a physical and metaphorical vault, restricting access to knowledge (Wheeler 13).

Darwinian evolution is referred to by Tom Wheeler when discussing the evolution of network technology in his book “From Gutenberg to Google: The History of Our Future”. He writes that “the evolution of network technology mimics the step-by-step natural evolution of living things, referencing a quote about natural selection written by Charles Darwin. The quote goes “it is the steady accumulation, through natural selection, of such differences … that gives rise to all the more important modifications of structure”, and Wheeler mentions that Darwin “could have been describing technology as well as biology”(Wheeler 16). In doing so, Wheeler is suggesting that the evolution of humanity and the evolution of communication networks such as print are inextricably linked.

Photo credit: Sofia Nyquist, taken at the archives of the International Fashion Research Library in Oslo.

Pre-digital periodical: referring to periodicals produced prior to the digital production methods popularized by digitalization (periodicals published before ca. 2000); these publications tend to contain physical, visual, and narrative elements rooted in the absence of digital media at their time of production.

Post-digital periodical: referring to publications printed in an era when communication networks have undergone the evolutionary development of digitalization (periodicals published after ca. 2000); periodicals of this era often contain elements which differ from pre-digital periodicals as a result of the influx of digital media in the landscape of communication networks.

The Purpose of Print

In our post-digitalized world, printed media still exists, albeit changed by the evolutionary forces of digitalization. Dissecting and deconstructing the pages of periodicals published during the past thirty years allows us to gain a deeper understanding as to how printed media has evolved in response to the influx of digital media.

Categorizing publications by those printed before and those printed after the rapid digitalization of the early twenty-first century, I will distinguish their differences by defining them as either pre- or post-digitalized periodicals.

Amongst the most notable differences between pre- and post-digitalized periodicals is their turnover rate. Pre-digital periodicals were often produced monthly or bimonthly, reflecting the fast production and consumption rate at the time. Quick turnover indicates not only the rate of consumption, but the purpose of the magazine: to sell content. In a post-digitalized world, the term ‘content’ has come to evoke the digital spaces through which it is frequently experienced: websites, social media, and influencer culture. However, in a pre-digitalized world, printed media (along with television) was the primary networking medium responsible for marketing to consumer’s escapist desires.

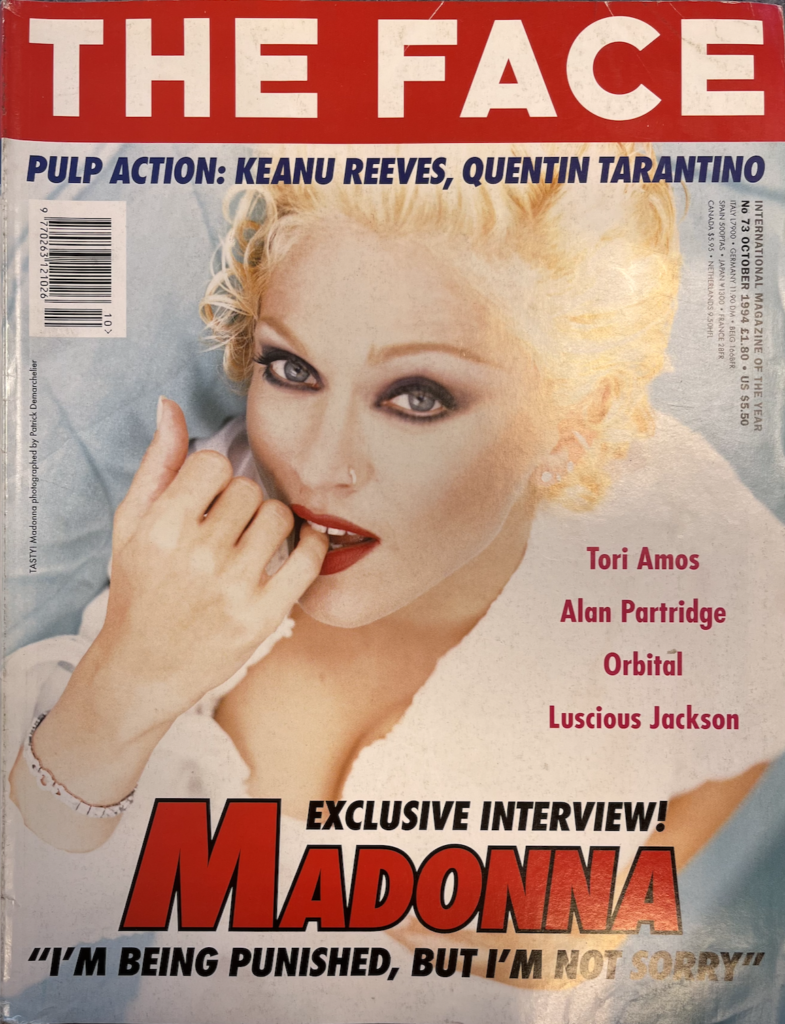

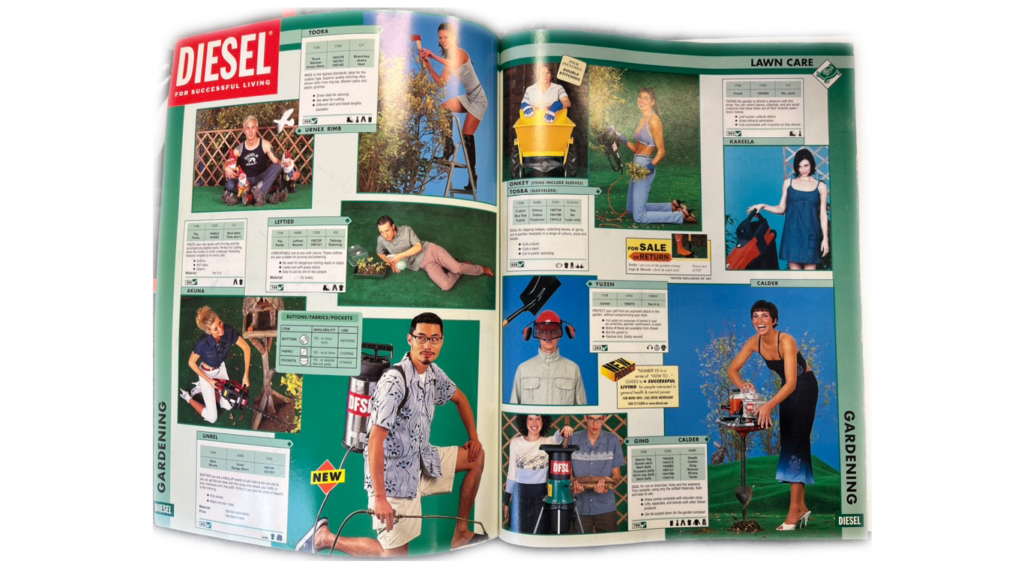

As a marketing tool, the profitability of a magazine was imperative; indeed, the entire body of a magazine was, in and of itself, a manifestation of consumerist objective. The pages of pre-digitalized periodicals from the 1990s reflect the desire to captivate and appeal, instigating subsequent rises in the sales of both future issues and advertised products. Various publications—including Dutch Magazine and The Face—demonstrate this through both their materiality and content.

Active participation is contrary to passive participation. To be active one must intentionally engage with a material; one must act upon the object, allowing for a unique interaction between the presented media and one’s personal thinking and experiences. To be passive is to allow the the material to act upon you, allowing your subconscious to be guided without engaging critically with the presented media.

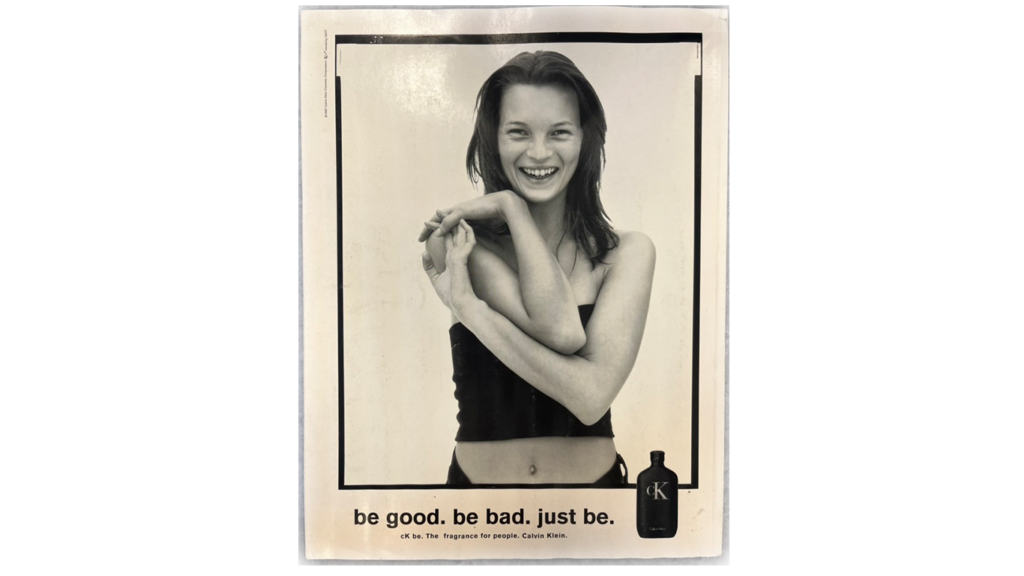

Post-war advertisements: after WWII, in an attempt to bridge the gap between supply and demand, advertisers switched from using text heavy advertisements to using image driven advertisements. This was a means to reach the subconscious human desire for belonging and respect, thus appealing to emotion rather than logic. Such advertisements often focused on the traits of the products user—images of beautiful, successful, happy, and respectable models would, through visual translation, become qualities inherently tied to the product being sold.

Example of a pre-war advertisement. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Materiality signifies an agenda of sales through the commodification of its pages. Virtually all pre-digital periodicals pertaining to fashion and culture have been printed on a thin, glossy paper. Being produced bimonthly, the choice of paper was certainly a means to cut costs in the production of such periodicals, but it also denotes the magazine as an object of surface value.

Being made from a cheap paper subordinately establishes the pre-digital periodical as a cheap object—one to be used and disposed of. There is surface value in the magazine’s ability to capture the reader through the glamorization of its pages, quite literally glossing over the contents to extend its appeal; however, beneath the shiny surface remains a cheap paper. Thus, the materiality of the pre-digital periodical directly reflects its primary purpose: to be a medium by which an audience may be engrossed by its glossy images but holding no greater material value than its ability to successfully entertain and advertise.

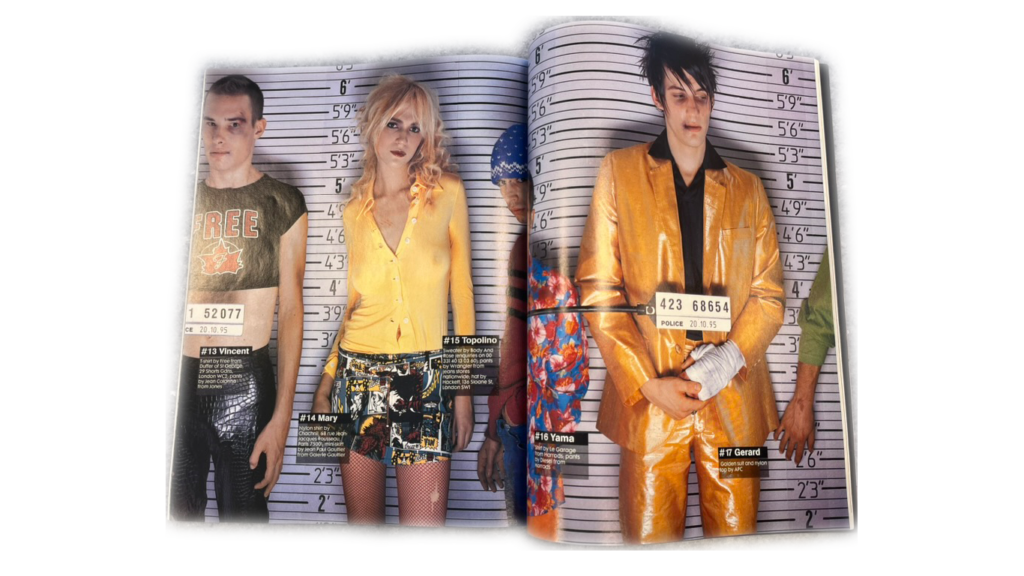

In terms of content, the central element present in pre-digitalized periodicals is image. This is similar to contemporary digital media platforms, and further distinguishes pre-digitalized periodicals as a medium for marketing. Unlike blocks of text, images are easily digested and engaging, capturing readers’ attention without requiring their active participation. In this sense, images relate back to rates of consumption as they are immediate—both in terms of entertainment and invitation to consume.

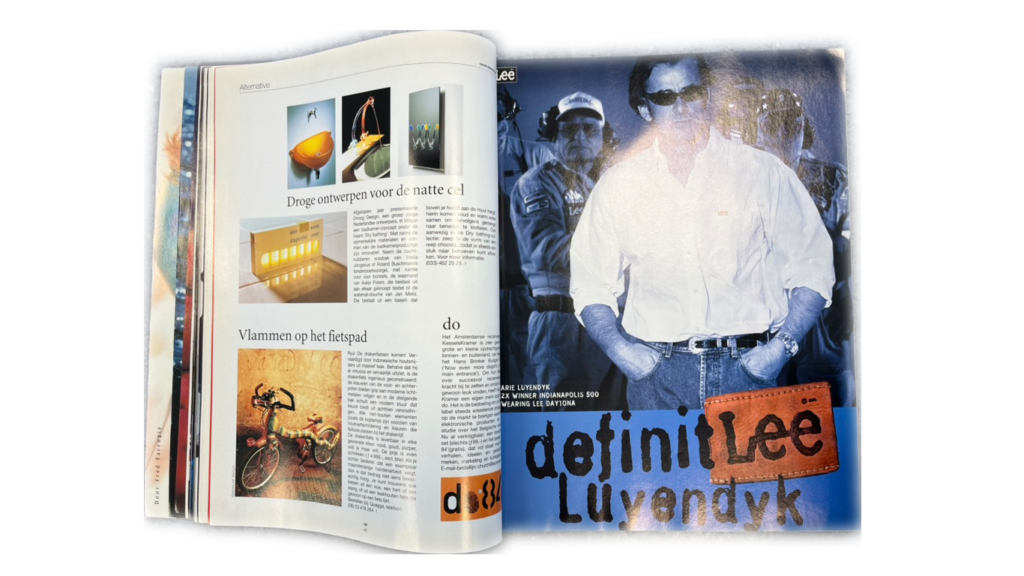

In issues no.14 and 25 of Dutch Magazine, a bimonthly fashion magazine which ran from 1994 until 2002, a large majority of pages are filled with such images. A two-page spread of bold colors promoting the clothing of Diesel “for successful living” uses a collage of images referencing post-war advertisements in a classic play on consumerist agenda. Other pages feature oversaturated images, blown up images, and small images livening any pages of text with a pop of color.

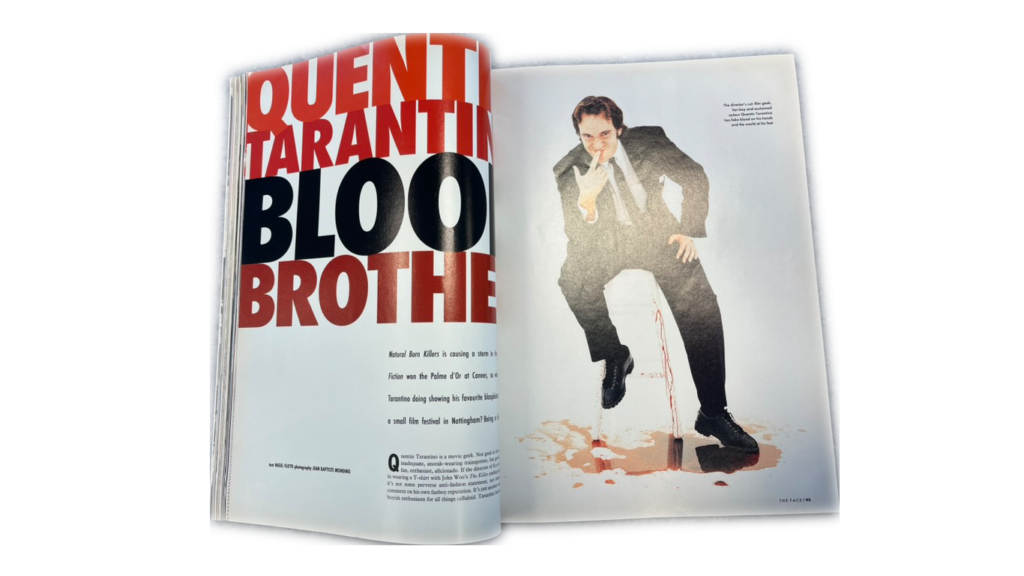

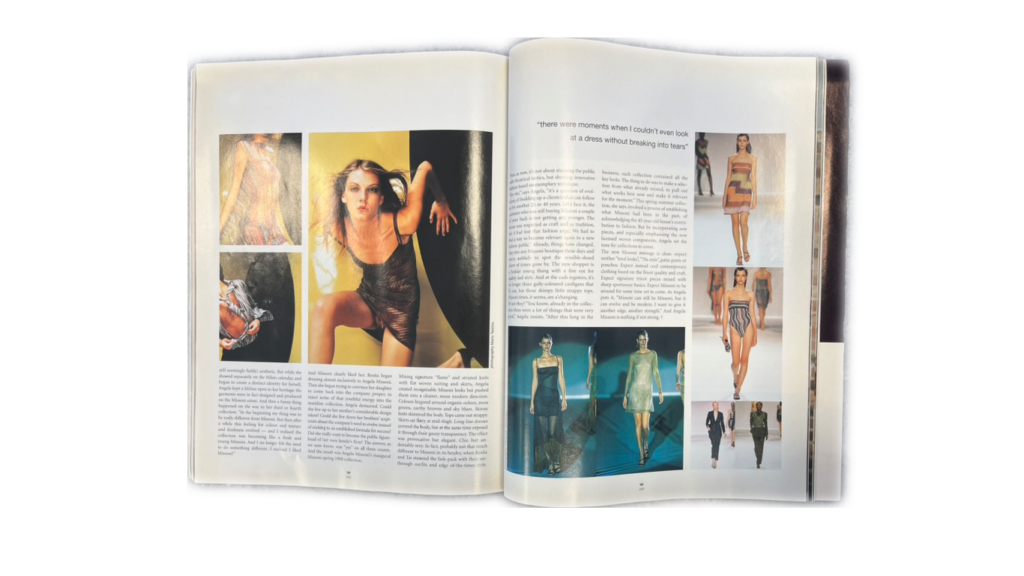

In issues of The Face from 1994 and 1995, we see much of the same content. It isn’t simply the presence of image which solidifies pre-digital periodicals as a medium of marketing—after all, printed media has always been recognized for its visual formatting. Rather, it is how the images act within the page. When compared to text, the image is much more adept to capturing a reader’s attention. This is partly due to the image’s ability to easily reach readers, but also due to the importance (or lack thereof) placed on text throughout these publications.

Where images are large and colorful, written texts are often small and indistinguishable. Several spreads throughout the pages of Dutch Magazine use text as a tool to guides readers to the next image rather than the words themselves. This is achieved by minimizing the font size of the text and placing it into visual boxes; by doing this, an illusion of visual object is achieved more so than an enhanced readability, thus the text can be easily skimmed over.

On pages where text has a greater presence, the words seem to aid in the selling of products or celebrity. This is often seen in The Face, which includes several stories covering stars such as Quentin Tarantino and Naomi Campbell. In these articles, the text acts as a gateway for more interaction; reading a five-page story about Tarantino will lead to ticket sales, and an article about the beauty and disaster of Campbell creates a desire to enter the world in which she exists (i.e. fashion magazines). Indeed, it seems that in pre-digitalized periodicals, the more visible the text, the more entertaining and marketable the words tend to be.

In this sense, digitalization has diminished the inherent need for print; it is much more efficient to use online spaces where content (as a marketing tool) can reach a potentially limitless audience without the extra costs of printing and distributing. Additionally, digital media allows for the ability to use various forms of image (i.e. animated images and video) while also providing direct access to products through clickable icons or hyperlinks, inviting more interaction thus more sales. As digitalization created a shift in the marketing industry, printed media was stripped of its primary purpose of selling products. In turn, a gap appeared for post-digitalized periodicals to evolve into something of greater sophistication.

Photo credit: Sofia Nyquist, taken at the archives of the International Fashion Research Library in Oslo.

Different Formats: Viscose Journal has famously published issues which resemble various objects such as purses and fans.

Photo credit: Sofia Nyquist, taken at the archives of the International Fashion Research Library in Oslo.

To keep their reader base, post-digitalized periodicals required a change in purpose, shifting their focus to cater towards intimacy and integrity in an increasingly algorithmic networking landscape. Just as purpose is reflected in the materiality and content of pre-digitalized periodicals, so it is also reflected in post-digitalized periodicals. Notably, the turnover rate of post-digitalized periodicals is much slower, with many magazines being published biannually. This is the first indication of a shift in purpose; slower production directly opposes that which creates most revenue, as it simultaneously slows consumption rates. Still, post-digital periodicals have continued to be published and sold, indicating that qualities besides the quick entertainment and marketing techniques of pre-digitalized periodicals were becoming prominent and desired elements in printed media.

Looking at the materiality of post-digitalized periodicals, it is clear that the quality of object has improved with the slower production rate. In The Gentlewomen, a magazine which celebrates contemporary women, the pages have a heavy weight and vary in textures throughout the same issue. Other magazines, such as Homme Girls and Viscose Journal, break the standard formatting of magazines by printing their publication in a much larger format or a completely different format. This attention to material detail emphasizes the magazine as an object, one which is meant to be experienced and interacted with on a personal level. Higher quality materials also reflect the time and thought put into the magazine, elevating it as a curated object of greater worth.

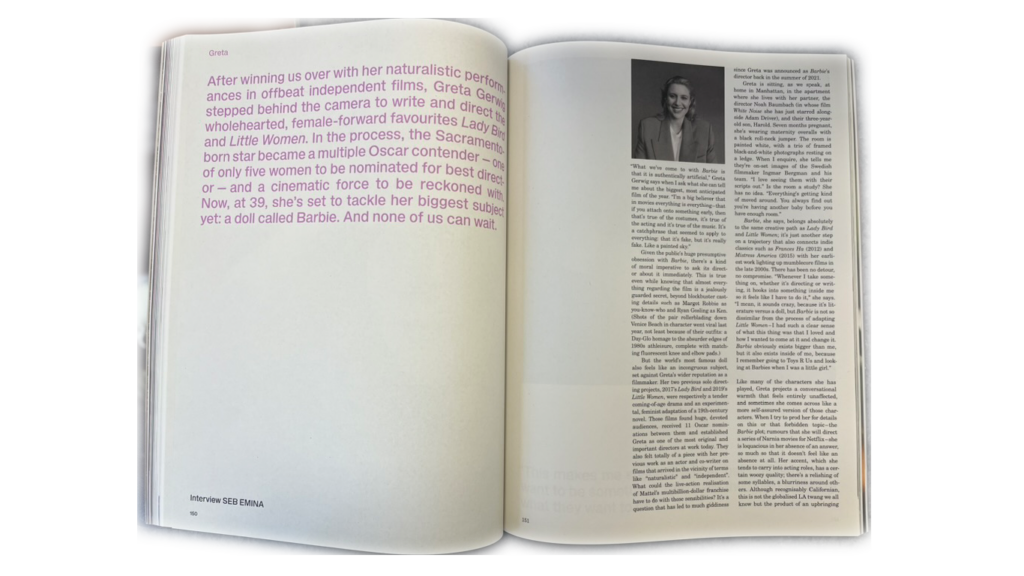

The content of post-digitalized periodicals also signifies a departure from that of pre-digital periodicals. Where pre-digital periodicals focused heavily on attention grabbing images, post-digital periodicals take a more contemplative approach. Entire issues can be dedicated to a certain topic; by carving out a specific niche for themselves, publications are able to pursue deeper connections both within the material they choose to discuss and with the readership they attract.